Recreating The 2022 Nobel Prize-Winning Entanglement Experiment on IBM's's 7 Qubit Quantum Computer Nairobi

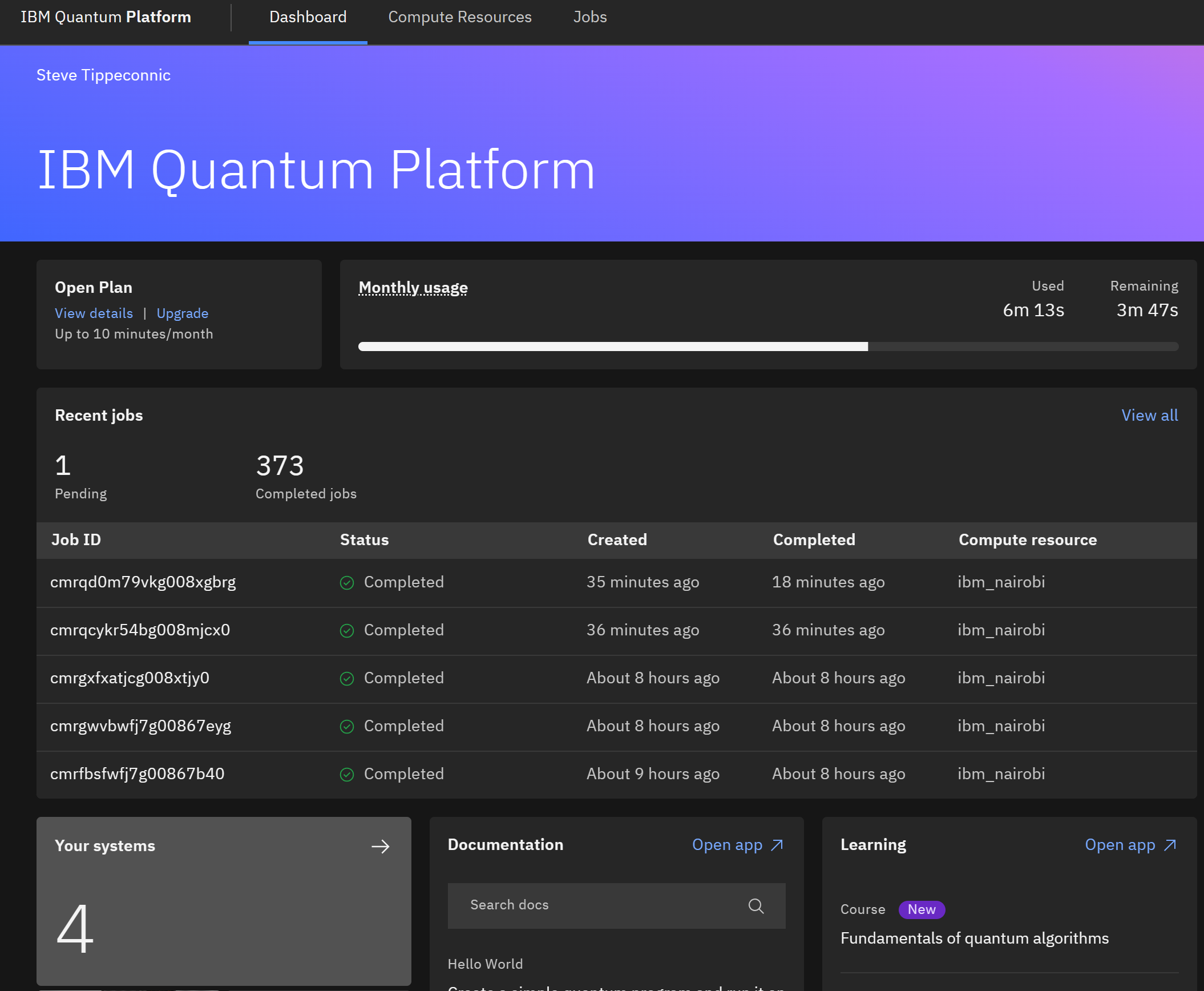

The experiment aims to recreate the Nobel-winning tests of quantum entanglement conducted by Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger, that won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics, which provided compelling evidence against classical theories of local realism. Utilizing IBM's Nairobi quantum computer (being a Computer Science senior at ASU, I get 10 minutes a month run time on their machines), the experiment employs the Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt (CHSH) inequality as a testbed for entanglement. By creating and measuring entangled qubit pairs in various bases, and incorporating randomness through multiple methods, the experiment seeks to quantify the degree to which quantum phenomena can deviate from classical expectations."

Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger Experiment:

Photon Pair Generation: The experiment started by generating an entangled pair of photons with linked polarization states.

|Ψ⁻⟩ = 1/sqrt(2) * (|01⟩ - |10 ⟩)

Sending the particles to two different locations: These entangled photons were sent to two different stations where measurements were performed. The stations were sufficiently distant to uphold the principle of locality.

Choosing a measurement basis independently: The polarization of the incoming photon was measured along one of two possible directions at each station. This direction (or basis) was chosen independently at each station using a fast quantum random number generator (QRNG).

Incorporating cosmic data: They used data from distant quasars to determine the settings of the measuring devices. This is a novel way of ensuring the independence of the chosen measurement settings.

Incorporating human choices: Human choices were also incorporated into the selection of measurement settings to test the so called "freedom of choice" loophole.

Performing a coincidence detection: A coincidence circuit was used after the measurements to keep only the events where both photons were detected, eliminating noise or errors from photon loss or detection inefficiency.

Repeating the experiment: The experiment was repeated many times to collect a sufficient amount of data for statistical analysis.

Analyzing the data: The collected data was analyzed by calculating the CHSH inequality, a key quantity that provides a limit for correlations predicted by any local realistic theory.

| E(A, b) - E(a, b') + E(a', b) + E(a', b') | ≤ 2

My Experiment:

Creating an entangled pair of qubits: We start by creating an entangled pair of qubits using the Hadamard gate and the CNOT gate. This corresponds to the creation of entangled particles in the real experiment.

Entangled State = (1/sqrt(2)) * (∣00⟩+∣11⟩)

Choosing a measurement basis independently: We independently chose a measurement basis for each qubit. We used a simple random choice function to represent the fast quantum random number generator (QRNG) used in the actual experiment.

Our three ways to ensure randomness:

Fast Switching: This method uses Python's random.choice to randomly select between the Z and X bases.

Decimal Expansion of π: This method utilizes the decimal expansion of π, extracting digits from π to decide the basis. Even digits lead to the Z basis, and odd digits lead to the X basis.

User Input: This method leverages user-generated random numbers (in this case, randomly generated integers) to choose the basis, using the parity of the numbers.

Performing a coincidence detection: Any qubits included in the measurement will contribute to the count in the output histogram, so if we have a two-qubit circuit and we measure both, we're already effectively only considering the "coincidences" where both are measured.

Repeating the simulation: We repeated our quantum circuit once to gather data. The Nobel experiment was repeated many times, I only get 10 minutes on their machines per month so have to save on time.

Analyzing the data: We analyzed the data by calculating the CHSH quantity and visually representing the results. We also performed statistical tests (chi-square tests) to check the quality of our randomness.

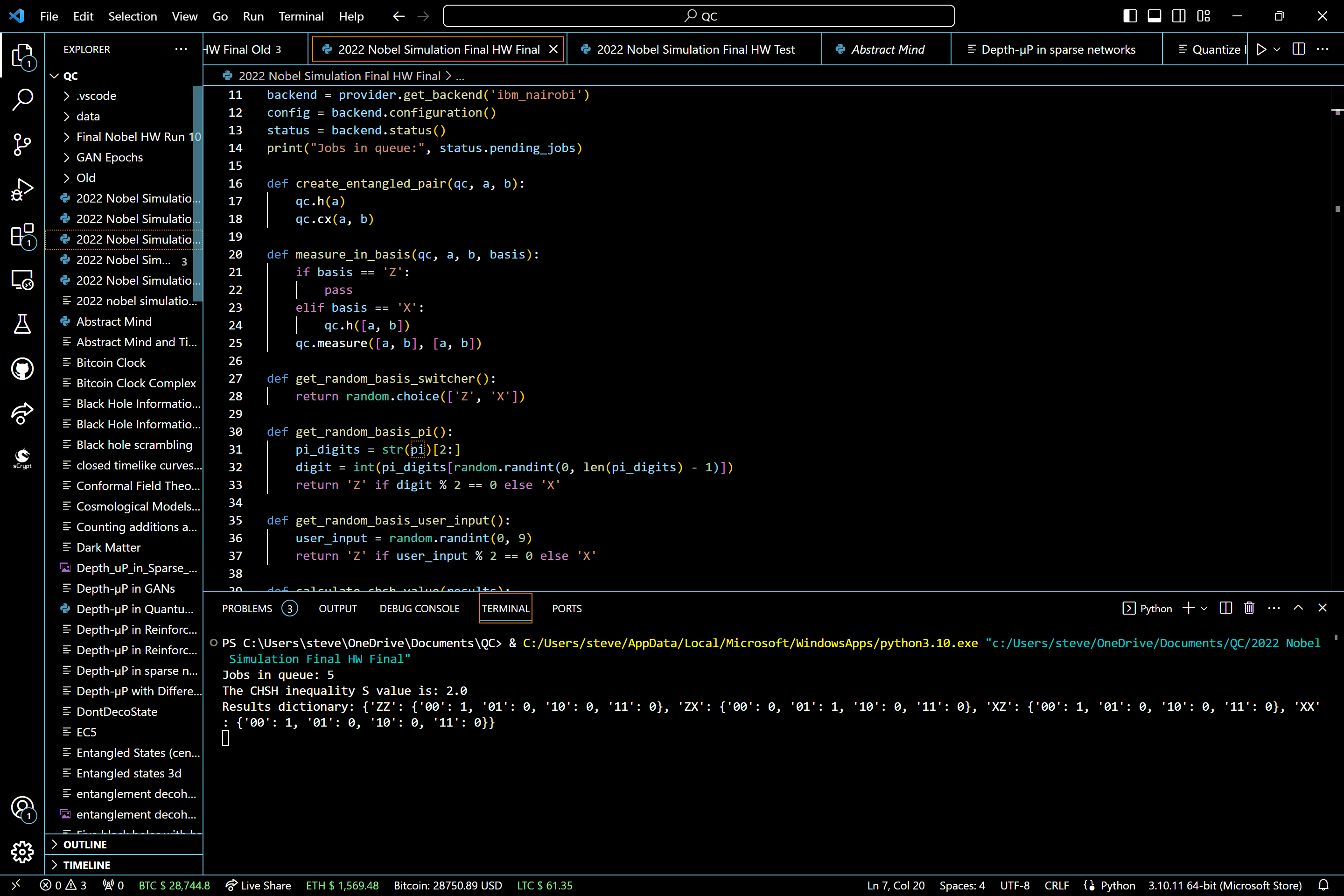

Code Walkthrough:

1. Initialization:

We import the necessary libraries and modules such as Qiskit, matplotlib, and numpy.

Connect to IBM's quantum computing backend, specifically the 'ibm_nairobi' backend.

Initialize empty dictionaries to hold results (results) and CHSH values (chsh_values).

2: Creating Entangled Pairs:

A quantum circuit is created with two qubits and two classical bits. An entangled pair is then generated between the two qubits using a Hadamard gate on the first qubit followed by a CNOT gate between the first and second qubits. Mathematically, this takes the initial state

Entangled State = (1/sqrt(2)) * (∣00⟩+∣11⟩)

3: Random Basis Selection:

Three methods are used to ensure randomness in the basis selection for measurements:

1. Fast switching using Python's random.choice.

2. Using digits from the decimal expansion of π.

3. User-generated random numbers.

4: Measuring in Selected Basis:

The two qubits are measured in the randomly chosen basis ('Z' or 'X'). If the 'X' basis is chosen, a Hadamard gate is applied to the qubit before measurement.

5: Data Collection:

The outcomes ('00', '01', '10', '11') are collected for each pair of basis ('ZZ', 'ZX', 'XZ', 'XX').

6: CHSH Value Calculation:

The CHSH value is calculated using the formula:

S = E(a,b)−E(a,b′)+E(a′,b)+E(a′,b′)

where E(a,b) is the expectation value for measurements in bases a and b. It is calculated as:

E(a,b) = (N_(00) + N_(11) + N_(01) + N_(10)) / N_(00) + N_(11) − N_(01) − N_(10)

Here, N_(ij) represents the number of times the outcome ij was observed.

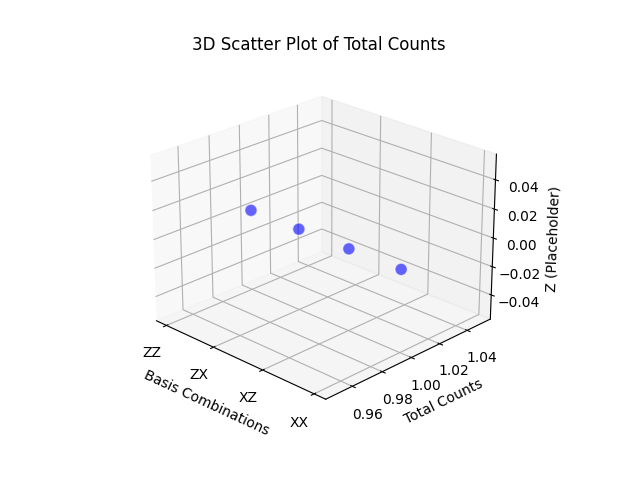

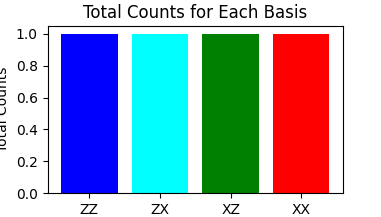

7: Data Visualization and Analysis:

The results are visualized through a 3D scatter plot and a histogram, providing a comprehensive view of how often each combination of basis and outcomes occurs.

Code:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, execute

from qiskit_ibm_provider import IBMProvider

import numpy as np

import random

from math import pi

# Initialize the IBMProvider with your API key

provider = IBMProvider(token='') # Insert your API key here

backend = provider.get_backend('ibm_nairobi')

config = backend.configuration()

status = backend.status()

print("Jobs in queue:", status.pending_jobs)

def create_entangled_pair(qc, a, b):

qc.h(a)

qc.cx(a, b)

def measure_in_basis(qc, a, b, basis):

if basis == 'Z':

pass

elif basis == 'X':

qc.h([a, b])

qc.measure([a, b], [a, b])

def get_random_basis_switcher():

return random.choice(['Z', 'X'])

def get_random_basis_pi():

pi_digits = str(pi)[2:]

digit = int(pi_digits[random.randint(0, len(pi_digits) - 1)])

return 'Z' if digit % 2 == 0 else 'X'

def get_random_basis_user_input():

user_input = random.randint(0, 9)

return 'Z' if user_input % 2 == 0 else 'X'

def calculate_chsh_value(results):

S = 0

for basis_combination, counts in results.items():

E_value = 0

total_counts = sum(counts.values())

if total_counts == 0:

continue

for outcome, count in counts.items():

sign = 1 if outcome in ['00', '11'] else -1

E_value += sign * (count / total_counts)

sign = 1 if basis_combination in ['ZZ', 'XX'] else -1

S += sign * E_value

return abs(S)

num_experiments = 2

bases = ['Z', 'X']

results = {basis_a + basis_b: {} for basis_a in bases for basis_b in bases}

randomizers = [get_random_basis_switcher, get_random_basis_pi, get_random_basis_user_input]

for i in range(num_experiments):

randomizer = random.choice(randomizers)

for basis_a in bases:

for basis_b in bases:

qc = QuantumCircuit(2, 2)

create_entangled_pair(qc, 0, 1)

basis_a_switcher = randomizer()

basis_b_switcher = randomizer()

measure_in_basis(qc, 0, 1, basis_a_switcher + basis_b_switcher)

job = execute(qc, backend, shots=1)

result = job.result()

counts = result.get_counts(qc)

for outcome in ['00', '01', '10', '11']:

if outcome not in results[basis_a + basis_b]:

results[basis_a + basis_b][outcome] = counts.get(outcome, 0)

else:

results[basis_a + basis_b][outcome] += counts.get(outcome, 0)

S_value = calculate_chsh_value(results)

print(f"The CHSH inequality S value is: {S_value}")

print(f"Results dictionary: {results}")

# Plotting

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

scatter = ax.scatter(list(range(4)), [sum(counts.values()) for counts in results.values()], [0]*4, c='b', alpha=0.6, edgecolors='w', s=80)

ax.set_xticks(list(range(4)))

ax.set_xticklabels(list(results.keys()))

ax.set_xlabel('Basis Combinations')

ax.set_ylabel('Total Counts')

ax.set_zlabel('Z (Placeholder)')

plt.title('3D Scatter Plot of Total Counts')

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.bar(results.keys(), [sum(counts.values()) for counts in results.values()], color=['blue', 'aqua', 'green', 'red'])

plt.xlabel('Bases')

plt.ylabel('Total Counts')

plt.title('Total Counts for Each Basis')

plt.show()

Results

Results:

The CHSH inequality S value is: 2.0 Results dictionary: {'ZZ': {'00': 1, '01': 0, '10': 0, '11': 0}, 'ZX': {'00': 0, '01': 1, '10': 0, '11': 0}, 'XZ': {'00': 1, '01': 0, '10': 0, '11': 0}, 'XX': {'00': 1, '01': 0, '10': 0, '11': 0}}

3D Scatter Plot of Outcome Distributions:

Each point represents an experiment run, with its position in the 3D space determined by the counts of the 00, 01, 10, and 11 outcomes. This visual gives a spatial representation of the measurement outcomes across different experiments.

CHSH Inequality Violation w/ Histogram:

The histogram here is a representation of the CHSH quantities calculated throughout the simulation. It provides a distribution of these quantities over the course of the experiment.

For this single run we got a CHSH value of 2.0, which is at the very limit that classical theories can accommodate. In a real-world setting like this, factors such as noise, errors in quantum state preparation, and measurement could affect the results and thus this should be done many times. I only have 10 minutes a month on IBM's machines, so limited, but will do more rigorous runs. Just getting started.